Fresh out of architecture school in 2012, I got an offer to intern at the San Francisco office of a big global design firm. I managed to eke out a living on an intern’s salary by living off of credit cards in a cramped room I found on Craigslist. My first substantial project was the renovation of an historic warehouse at 375 Beale Street in San Francisco’s South Beach neighborhood into a new shared home for several Bay Area regional agencies, dubbed the Bay Area Metro Center. Little did I know that it was the beginning of a four-year journey during which I would cut my teeth as an architect, get my professional license, and see the building completed and occupied.

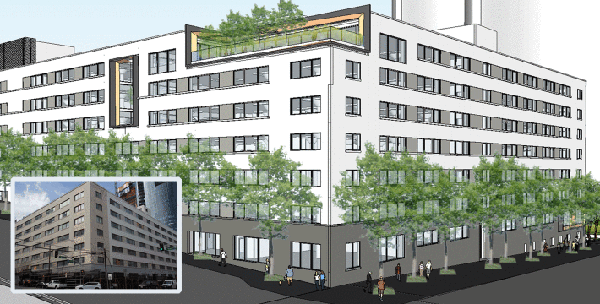

Before picture and rendering courtesy of Perkins + Will

It was a huge and complex undertaking. The Metropolitan Transportation Commission had picked an abandoned former U.S. Postal Service warehouse as the place to collocate its headquarters with the Association of Bay Area Governments and the Bay Area Air Quality Management District.

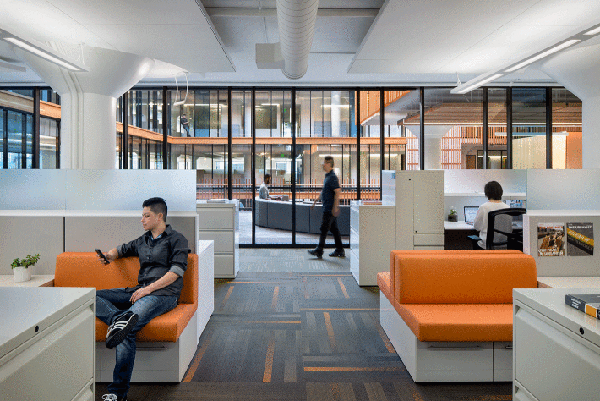

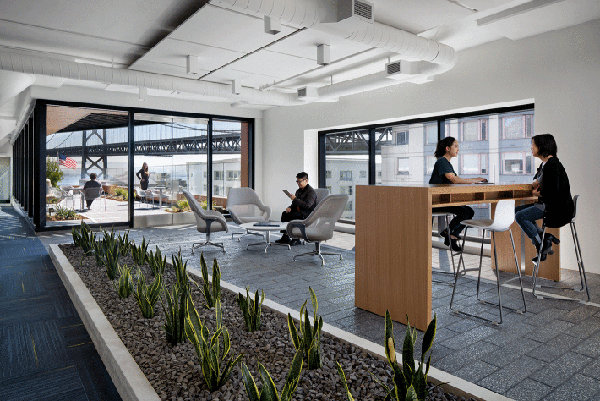

That meant this humongous, eight-story concrete warehouse—with floorplates that stretched across the width of a city block—had to be converted into contemporary office space. The big design move was to carve an atrium into the center to bring daylight into the floor plates, then create collaborative spaces throughout for casual interaction. Perkins+Will—the big global design firm I mentioned—was responsible for the shell and core, while TEF handled the interiors.

My responsibilities started with a humble assignment: drawing up diagrams and working on the building’s bike storage area. But as other staff members went on to other projects or other firms, I was asked to design a security desk, then the back-of-house spaces, followed by the main boardroom space.

Then, in the midst of construction, the project architect left. As the project’s new knowledge-bearer, I found myself loaded with architect-owner-contractor meetings, requests for information, and shop drawings. It was daunting, but during that time, I learned volumes about delivering a building project. Three sobering revelations in particular come to mind.

DESIGN DOES NOT STOP

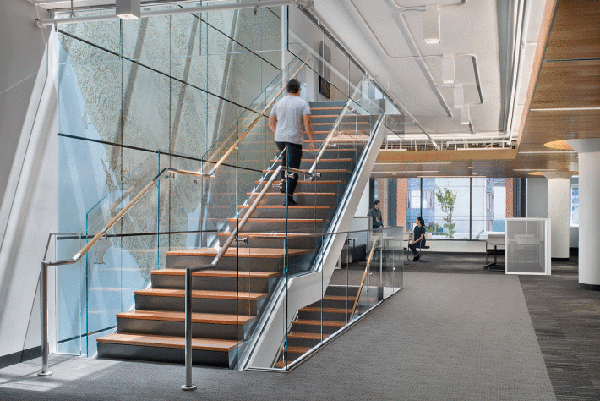

First there was a conflict between the warehouse building’s existing structural conditions and the smoke sensor and atrium sprinkler constraints. Long story short, details were re-imagined, which led to the transformation of the atrium design during construction. What was originally envisioned as a glassy atrium with rough concrete slab edges protruding at each floor evolved into a warm, wood-filled space. As architects and designers, many of us prefer the front end of a project. We enjoy creating renderings and big concepts, then move on. But design doesn’t necessarily stop once the drawings are issued. A project can very often morph and evolve until the ribbon is cut (and sometimes beyond that!), and construction can be a design exercise in real time.

IN THE AGE OF AUTOMATION, BEWARE THE COPY/PASTE

In the age of efficiency, firms are constantly looking to systematize and streamline the design process. At the same time, every drawing in a set will be studied by contractors and building officials, so we have to make sure not to automate our thinking when compiling our drawings.

With the Bay Area Metro Center, I learned this lesson sitting through accessibility reviews with the Division of the State Architect. Many of the project’s typical details needed updating based on various minor iterations of the code. Automatically copying and pasting details from previous projects soon proved to be less of a time saver than expected. As architects and designers, we need to make sure that protocols are in place to facilitate a streamlined process that also integrates thoughtful and conscientious quality control measures.

STEP BACK AND LOOK

It’s easy to get frustrated during a project’s construction. There’s real money and time on the line—it’s not like in architecture school. You’re constantly working to find common ground with the contractor and trying to pick the right battles. You’re focused intently on specific issues and details and sometime lose track of the larger scope. When these things bogged me down, I had to remember to step back and look at the big picture.

I remember the first time I saw something that I designed realized at the project. More than a year into the process, the construction site consisted of nothing more than concrete and dirt. I traveled to Oregon to visit the shop of the mill worker who was making the main security desk. To watch someone produce the wrapped, triangulated surface that I’d sketched up years ago was a well-timed reminder of why I was doing this. And now, to know that people are walking by it every day makes me proud.

The Metropolitan Transportation Commission and other agencies started moving to the Bay Area Metro Center earlier this year. With the completion of this project, I decided it was time for me to move on as well. I’d worked alongside TEF for years, and Andrew Wolfram had already made the leap from Perkins+Will to TEF. I felt there would be more opportunities at a small firm to work on projects from start to finish, and they’d be local, so I could see them taking shape in the physical world.

The role of the architect is changing, and many designers get slotted into one role over the long term. The legal requirements for the building industry have become so complicated that the number of specialists we need to rely on has grown astronomically. But I’m a big believer in the idea of the well-rounded architect: someone who can diagram, program, draw, design, take care of construction drawings, and then handle construction administration.

Although I occasionally grew tired of working on a single building over such a long period of time, the experience accelerated my understanding of project development. I could connect early decisions to their outcomes and learn from them, which is something I would never have experienced jumping from one project assignment to another. I think many young architects would be better fulfilled working on a project from contract to occupancy.